More than 25,000 refugees and asylum seekers from neighboring countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Somalia and others live in the Dzaleka camp, located 40 kilometers from Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi. Donors have been providing aid for this center for many years, and with other open crises and attention in other parts of the planet, in Dzaleka everything is beginning to be lacking. Above all because people do not stop arriving: in recent times an average of 400 people a month, although fortunately the number of those who leave it generates a kind of balance in the total number. CARLOS MARTINEZ

The data on the saturation of the field are patent: there are 24 water wells for more than 25,000 people, so it is common to see queues like the one in the image to obtain liquid. The medical center, designed to serve about 10,000 people, is also overrun. And more and more things are missing. "The food does not arrive, the medical center is not adequate, I do not even have soap to wash clothes and, with the cold [in the present winter season the temperatures drop to 8º] we do not have blankets", says Francine, a 23-year-old single mother from Burundi who has spent her entire life in refugee camps. This is the third one it goes through. “In the other places they met our needs. Here life is very difficult and nobody comes to see how we are, ”he complains. CARLOS MARTINEZ

A man collects cardboard from the Dzaleka distribution center after a distribution of blankets and other supplies. "Before we focused on meeting the most basic needs," explains Enid Ochieng, head of UNHCR in Malawi. "Now, we don't even get to that." Due to budgetary constraints, the newcomers have practically nothing to raise a roof with and UNHCR, which manages the compound together with the Malawian government, has trouble even providing them with plastic tarps. “Donors have been helping here for many years. And there are other crises [even in Malawi itself, through whose southern border thousands of Mozambicans flee from violence] which makes it not so easy right now to sell Dzaleka to the world again, ”says Kelvin S. Sentala, assistant to Unhcr field. CARLOS MARTINEZ

Several women, with the elements that they have just received from the agencies present in the field, such as the World Food Program (WFP). The inhabitants of this camp who cannot be rehoused in other countries (that is to say, the great majority) depend almost exclusively on humanitarian assistance. The Government of Malawi, open to welcoming despite the serious problems facing the country, does not allow refugees to leave the camp or get a job. This leaves many without the possibility of subsisting or generating their own income. Some, like 35-year-old Somali Raheem, have been here since 1996 and no longer remember what it was like off the field. "I try to do things for myself that give me something to eat," says the father of a daughter who was born two years ago in Dzaleka. " CARLOS MARTINEZ

The length of time (in some cases, decades) that many have been in Dzaleka and the need to find a means of subsistence have led to the emergence of market areas within the enclosure, which are also visited by neighboring populations in the countryside. Many seek to exchange goods or get some money through the activity that is generated there. CARLOS MARTINEZ

A girl in front of a makeshift food stall in Dzaleka. Providing food to the inhabitants of the enclosure is a priority that, for now, is only covered until August, according to the World Food Program. From June to December of last year, the rations - already limited to only the basics: corn, legumes and vegetable oil - had to be cut in half. "This is an almost forgotten story, and we did not get more donor support," insists Mietek Maj, WFP's Deputy Director in Malawi. Lack of food is the main complaint of the refugees. CARLOS MARTINEZ

The first to arrive in Dzaleka, starting in 1994, found buildings and shelters built on the site of this former prison. Today, however, most have to build their own roof. And it is not easy because there are no funds or facilities. The land is also becoming scarce, given the number of people that have to be housed in just over 200 hectares. Upon arrival, the refugees are housed for several days in a poorly equipped and completely overcrowded transit center before getting their own space. In the image, construction of a shelter with bricks that are also produced in the field itself. CARLOS MARTINEZ

The medical center, designed for 10,000 people, cares for more than 60,000, counting on the inhabitants of neighboring communities. In practice, the peaceful coexistence of asylum seekers and refugees with Malawians from nearby towns has led the former to begin a real (though not yet legally supported) integration into the country. Coexistence in the countryside, a priorio complicated with ethnic, language and religious differences, is not too problematic. Everyone has been through traumatic experiences and they don't want any more trouble, explains 35-year-old Somali Raheem. What they are looking for in Dzaleka is security. CARLOS MARTINEZ

A young man works on the construction of a shelter in Dzaleka. Working is not only a necessity to obtain means to earn a living, but also a way to regain self-esteem and self-confidence. For this reason, and to limit dependence on the increasingly scarce aid, the agencies present in the camp yearn for a relaxation of the Malawian law that allows refugees to work in the country. Although there was a promising moment, for now the legal change is stagnant. The Government has decided to merge the reform of this regulation and that of immigration policies (such as the reception and transit of migrants bound for South Africa) and other issues into a single process, leaving it bogged down in Parliament for now. CARLOS MARTINEZ

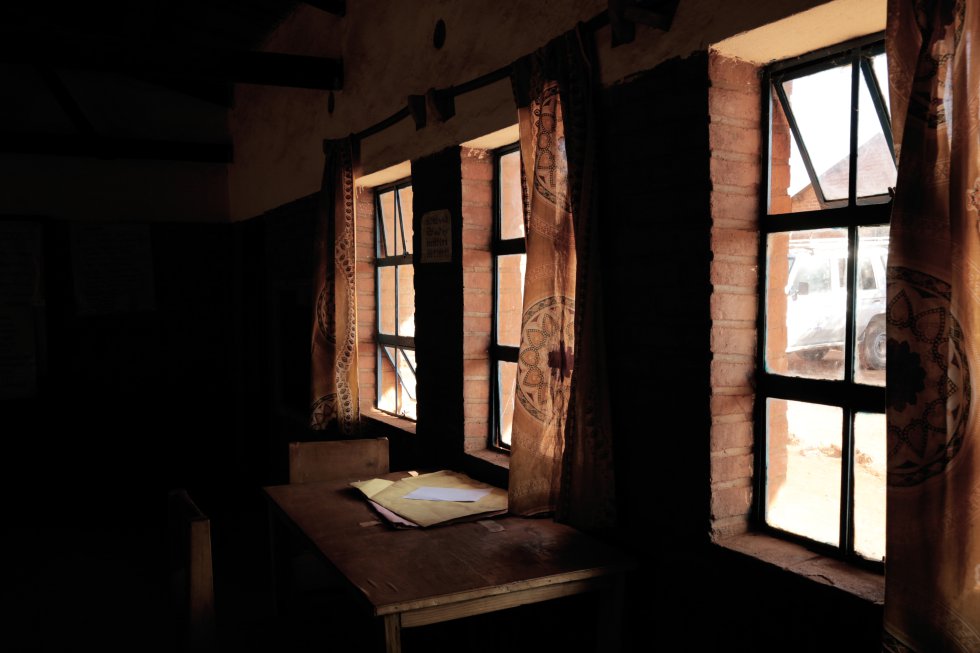

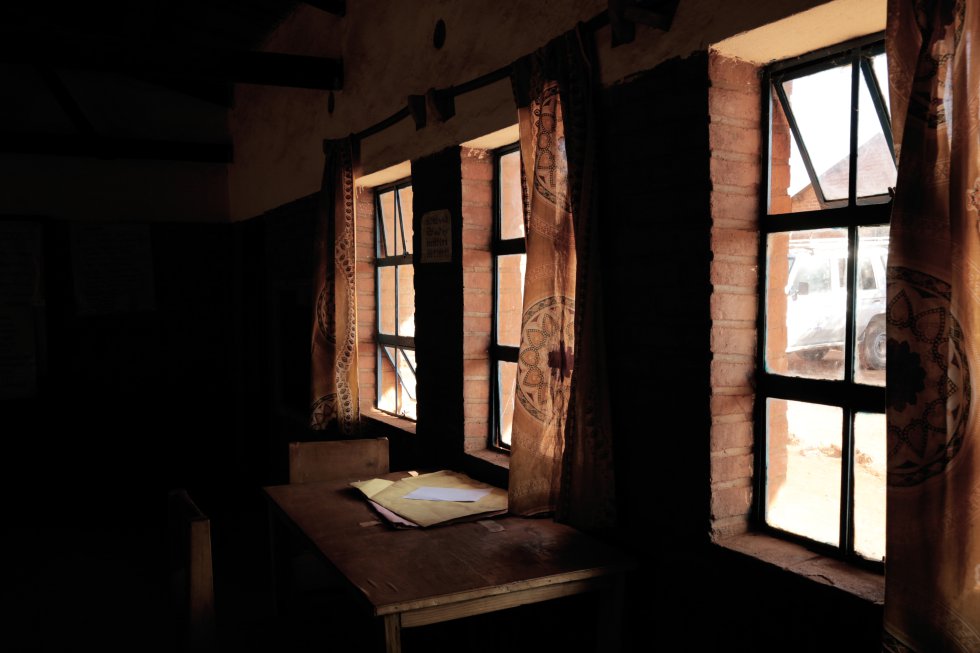

With one teacher for every more than 80 students, the primary school run by the Jesuit organization JRS has to take turns serving everyone. There are no classrooms, facilities and teachers, and absenteeism forced by the circumstances of life in the countryside is one of the problems. Boys like Dany, 16, are still in elementary school, because life has not allowed them to move faster. Dany likes English, math, and science. And he smiles when he tells that now he is usually the first of the class and that he would like to go to the university in the country. CARLOS MARTINEZ

In Dzaleka there is also a secondary school and other services, such as adult training. Teen pregnancies are a problem for girls of that age to attend class. Like almost everything here, the training centers serve both rural residents and Malawians from neighboring towns, who also suffer from need in many areas, but at least are free to work. CARLOS MARTINEZ

The educational offer in Dzaleka is completed with an 'online' university, in which up to 30 people a year enroll in three-year degrees through the internet endorsed by American universities such as Regis. They are courses that will allow them to specialize in areas such as education, business or social work. Vocational training and other courses are also offered. It is an option for some to continue preparing to obtain a job in the future if there is finally a legal change, in which, apart from the relocations in other countries (increasingly limited or more focused on other emergencies from other places) it seems to be the only way to alleviate the situation in the Malawian countryside. CARLOS MARTINEZ

Originally published on elpais.com

Post a Comment